Christian Revolution and Apocalyptic Pacifism

Ruminations on "Here I will justify violent revolution"

When I read The Case for Christian Nationalism by Stephen Wolfe a few months ago, I laughed out loud when I reached the golden line, “Here I will justify violent revolution.” Be the argument right or wrong, something about introducing the chapter so bluntly tickled me with some minor glee.

Since then, however, I have reflected on the argument itself. Most of it is pretty standard fare for early modern political thought: you will find the same basic moves in all kinds of thinkers, from at least the Reformation onward, though considerable variety in some of the details or the assumptions about how they would apply to given concrete circumstances. Thus I wish to pass over gladly the question of whether revolution can ever be justified, and further whether violent means to revolution can ever be justified, both of which are easy enough for most modern American Christians (including myself) to grant.

The more interesting questions come near the end of the main argument: whether it is permissible to start a revolution in defense of true religion, and whether it is justifiable for a Christian minority to by revolution establish a Christian government over a resistant majority regardless of their consent.

The former of these I am less interested in at the moment, except to say that I have some reservations about the line of argument Wolfe uses. On the one hand, from a classical two kingdoms and natural law perspective, I fully agree that a tyranny which attempts to forbid the basic exercise of our most fundamental religious duties is a violation of the most critical of natural rights, a principle we could know and act on even apart from special revelation, and on that level potentially among the most weighty of offenses which could factor into a justified revolution.

On the other hand, I am less certain about the distinction made between advancing the kingdom of God by the sword and defending it so. While certainly the two are formally different, and we should refrain from any sophistry which pretends that self-defense and aggression are equivalent, the most directly relevant text in the New Testament on the matter seems to address the latter:

My kingdom is not of this world. If My kingdom were of this world, then My servants would fight, that I would not be handed over to the Jews. But now My kingdom is not from here.

John 18:36

These verses have seen a truly ridiculous level of abuse in the interests of pacifism, quietism, and secularism, but as the classic prooftext that arms do not advance the kingdom of God, it actually specifies its interest as why Jesus’ disciples did not use violence to defend Him. If, then, defensive force for the kingdom is justified while offense force to advance it is not, something which I am not unwilling to consider, the argument should probably be further fleshed out.1

Of far more interest to me is the final step of the argument, justifying a Christian nationalist revolution to institute minority Christian rule contra the consent of the majority. This ground strikes me as far less secure than any other step. I admittedly have scratched my head a bit at this part, for example:

The reason is that although civil administration is fundamentally natural, human, and universal, it was always for the people of God. Civil administration was created to serve Adam’s race in a state of integrity, as an outward ordering to God. Today, those who are restored in Christ are the people of God. Thus, civil order and administration is for them.

This could be taken to mean either that civil order is only for the sake of Christians or that it is chiefly for their sake. It is not entirely clear to me which is intended. I think the latter would make the most sense, for the former would seem to rule out entirely the legitimacy of civil orders constituted by pagan peoples for themselves, a move which Wolfe would not make as I understand him. But if we take the latter route, the next move of a Christian minority simply being able to entirely and unilaterally overrule consent of the majority seems a leap too far.

I want to be clear here: I do not at all disagree with Wolfe that Christians actually have priority in political justice on account of being a restored form of mankind more inline with God’s original design. Nor do I disagree in principle that it may be right for a minority to impose their will on the majority if they are so able and the cause is truly just. Nor further do I even necessarily disagree that insufficient consent must not indefinitely postpone the establishment of a legitimate political order.

My objection is two-fold: First, for the reason mentioned above, unless the kind of priority of purpose that Christians have in civil order is total, being not priority but an exclusive right, then it does not seem clear that as Christians they should be able to entirely exclude the consent of the godless majority from playing a role in the constitution of their government. At minimum some kind of concession to their general consent seems necessary, lest they be some kind of slave class. Even a baseline level consent of “If you don’t like it, you are free to leave” should suffice in some cases, perhaps. It is not clear how, unless political authority is entirely abolished in unbelieving mankind, it could be just to deny them any right or role at all in the order necessary to obtain their natural goods and secure their natural rights.

Second is also a more basic problem: it is generally unwise to perform actions which one knows in advance are unlikely to achieve their primary ends. This is even more true, and may rise to the level of injustice, when those actions involve coercion or violence (think just war principles). Now, it should go without saying that the ends of civil government cannot be well fulfilled, if at all, where the people generally do not recognize the legitimacy of their laws and rulers, or where there is great unrest and rebellion on a regular basis.

This is the chief risk, not only practical but moral, of a minority Christian nationalist revolution. Unless you can persuade most people that, at bare minimum, your new regime is somewhat legitimate, somewhat representative of their interests, and somewhat deserving of recognition and obedience, to the point that they would prefer keeping it over other options (e.g. another revolution), you build a castle in the sand. And building sandcastles is both foolish and, if building with blood, unjust.

If the nation is unstable because most of the people are unwilling subjects of the new regime, then, it is likely to fall apart on its own. If the majority sentiment is sufficiently negative, you could be facing such extreme pushback that the only options to save the regime would be brutal suppression or civil war. But this brings us into very dark territory where it is not clear there is any remaining room for justice. If the character of the nation’s majority is such that this situation is a plausible result, it calls into question the justice of using violence to establish it.

This doesn’t, I should note, categorically rule out the kind of revolution Wolfe describes. It is possible that at the right moment, with the right critical mass of supporters, in the right situation, you could pull off a minority led revolution establishing a Christian government that would overcome the initial consent deficit to establish an order which the people would sufficiently tolerate to make achieving its goals feasible. If someone saw the signs that such times were at hand and decided to undertake the revolutionary project, then I do not doubt it could potentially be just and even good. Whether those times are in the cards for 21st century America I do not claim to know.

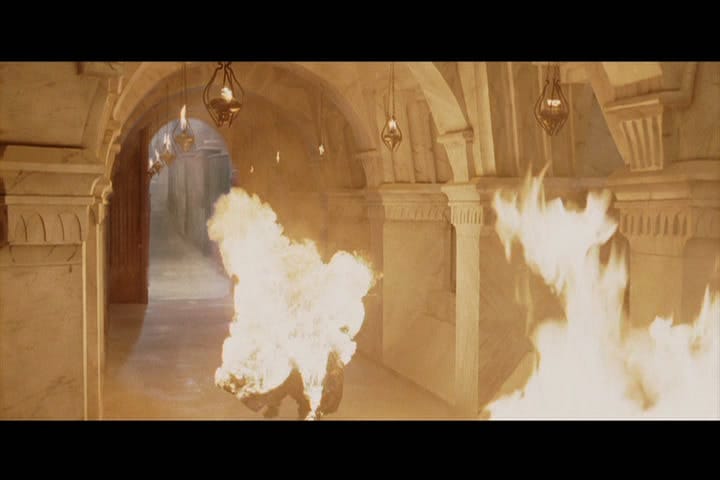

But what do we do if the time isn’t at hand? I share Wolfe’s concerns about simply sitting on our hands and doing nothing, idly sitting by while the West burns. It doesn’t pay to be Denethor.

As it turns out, though, Wolfe provides us another option, albeit in passing. Near the end of the chapter, explaining why Paul is silent about a potentially justified Christian revolution, Wolfe cites Thomas Aquinas to say that revolution is not always feasible, and in that case we must simply wait on God to deliver us. Here is a slightly fuller quotation of the cited passage in De Regno:

Should no human aid whatsoever against a tyrant be forthcoming, recourse must be had to God, the King of all, Who is a helper in due time in tribulation. For it lies in his power to turn the cruel heart of the tyrant to mildness… Those tyrants, however, whom he deems unworthy of conversion, he is able to put out of the way or to degrade, according to the words of the Wise Man: “God has overturned the thrones of proud princes and has set up the meek in their stead”…

But to deserve to secure this benefit from God, the people must desist from sin, for it is by divine permission that wicked men receive power to rule as a punishment for sin… Sin must therefore be done away with in order that the scourge of tyrants may cease.2

This passage helpfully frames the case. After first saying that a tyrant can be removed by all the people, or else by a higher authority, Thomas leaves as the final option waiting upon God in prayer and repentance. (As an aside, he is also very clear that private persons or sects have no right to regicide, and a tyrant can only be rightly deposed by the people as a whole. How Wolfe parses this probably goes back to my former question about the political status of a godless majority.)

The whole issue reminds me of N. T. Wright’s portrait of Jesus’ message in Jesus and the Victory of God. (I read this quite some time ago and feel too lazy to look up the details, so correct me if necessary.) He pointed out that her eschatological revolutionary ambitions were a big part of what Jesus expected Israel to repent of. Pagan imperialism was “too big to fail,” at least by traditional means. Israel would need to wait on God to act. But in Jesus God was acting, and by Christ’s death and resurrection, then the outpouring of the Spirit, the Church was empowered to conquer the Roman Empire by a different method than had been expected, using spiritual rather than physical swords.

This leads in to how I, influenced by both Wright and Andrew Perriman, tend to take Jesus’ “pacifistic” teachings. Though I accept the classical Protestant views of the core principles these teachings express (particularly Luther’s two-kingdom take), my contextual reading of how Jesus was applying these to his audience is shaped by this redemptive historical setting. Israel had neither a natural capacity nor a supernatural promise of aid to overthrow pagan imperialism by arms, therefore violent revolution could not be justified. Without the justification for a revolution, they ought to have focused on persuasion backed up by peaceable lives, robust purity of heart, and love of neighbor, that their light might shine before men, who would see and glorify their Father in heaven. And when the Church was filled with the Holy Spirit, she proceeded to do exactly this, eventually replacing pagan imperialism with Christendom. When Israel tried the unjust revolution method, they failed and were punished.

Coming back to Wolfe’s proposal, then, I think the Big Question™ comes down to feasibility. In principle, I think he is probably correct that under certain circumstances a minority-led Christian nationalist revolution against the will of the majority could be justified. But it is hard for me to imagine it being true of many cases because the probability that any resulting civil order would be extremely unstable seems very high.

The matter seems to come down largely, then, to reading the signs of the times. Right now, could a Christian nationalist revolution achieve its ends? Or would it be more likely to break things and create further violence and trouble by antagonizing the masses? I honestly don’t know. And that ambiguous space is where we can debate, poll, study, pay attention, and in the meantime cultivate the kinds of relationships that will benefit us and our nation whether we end up revolting or waiting on God, friendships and loves that will enrich life both in this socio-political order and whatever order follows it.

It might even be something as simple as making the distinction between violence in defense of the visible kingdom of God qua kingdom of God and violence in defense of the natural right to worship God.

Thomas Aquinas, De Regno, §51-52.